Knee pain is one of the most common complaints we treat in physical therapy.

One study looked at the frequency of knee pain and found that a quarter of the population had significant knee pain at one time or another. This can turn into a fitness roadblock - and can get in between you and the activities you love. Whether this means golf, tennis, lifting, running or even walking, we've seen knee pain put a stop to it all.

When It comes to understanding the knee joint, patients wonder what there is to understand. From a distance, the knee joint seems pretty simple. The joint straightens and bends. It doesn't have to control as much motion as the shoulder or hip.

When It comes to understanding the knee joint, patients wonder what there is to understand. From a distance, the knee joint seems pretty simple. The joint straightens and bends. It doesn't have to control as much motion as the shoulder or hip.

As we look closer at the knee, however, we find that the knee is more complicated than we thought. One may argue that this may be one the most complicated joints in the body. Luckily, we are going to break this joint down and hopefully give you an idea how the knee functions.

Breaking Down A Complex Knee Joint

Today's post will cover the function of each part in the knee. If you get lost, we encourage you to pause and look up pictures or definitions of these structures to increase your understanding.

Realizing that you may have specific issues in mind, we placed multiple explanations and common issues within this post to help as many of you as possible. Please reach out to us if you have any questions.

The Parts

Before we go into the specific joints involved with the knee, we need to know what bones make up the knee joint. These include:

- The Femur (also called the thigh bone)

- Tibia (also called the shin bone)

- Fibula on the outside of the shin, and

- the Patella ( also called the knee cap). Some of these bones may sounds familiar. That's because the Femur is also part of your hip joint, and the Fibula and Tibia make up the majority of your ankle joint.

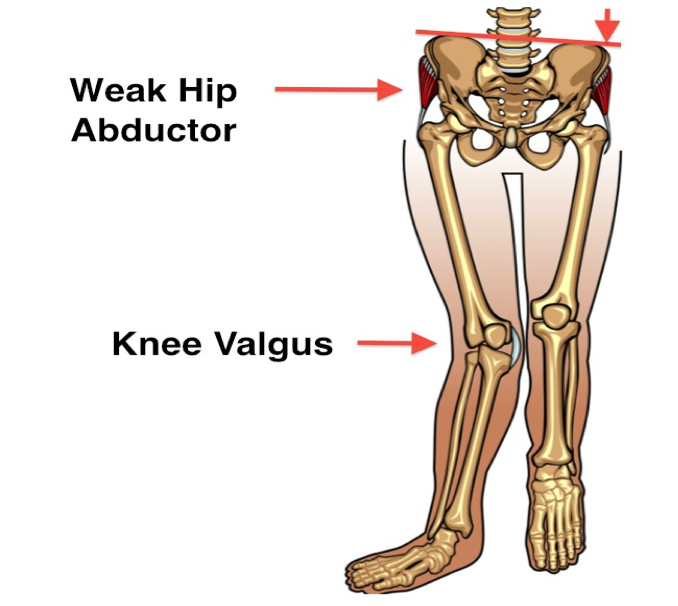

Ever wonder why your Physical Therapist looked at your ankle and hip, when you came in for knee pain? The reason is these three joints directly affect each other. We have seen plenty of patients with knee pain, whose main problem is actually their hips or foot.

The bones that make up the knee are important because these are the potential parts where a fracture could occur. A fracture is defined as any break in the bone and can range from a hairline fracture that can be hard to see on a x-ray, to a compound fracture requiring surgery. Knee fractures need to be addressed quickly and can be ruled out by a trip to your Physical Therapist.

Tibiofemoral Joint

Your tibiofemoral joint is what most people think of as the main knee joint. This consists of the Tibia (also called your shin bone) and the Femur (also called your thigh bone). These joints meet together to form the main joint that bends and straightens your knee. This joint, just like the shoulder, is a synovial joint. This means the joint surfaces are covered by cartilage to increase cushion and are surrounded by synovial fluid. This fluid is the "oil" that decreases friction between the bones.

Wait... that's it? That wasn't complex at all!

It is important to understand there are three main compartments in the knee. Two of them are in the Tibial Femoral joint, and one of them is underneath the Patellofemoral joint. This can help explain how someone can have knee arthritis in one, two, or three compartments (uni, bi, and tri-compartmental).

The knee joint is also stabilized by a complex combination of muscles, ligaments, natural cushioning, and tendons. All of these supports occur inside the joint lining (intra-articular), or outside the joint lining (extra-articular). To make this as simple as possible, lets start with what supports the knee outside the joint.

Extra-articular Parts

There are two main ligaments that support the knee from outside the joint. These are called the Lateral Collateral and Medial Collateral ligaments, or LCL and MCL. The LCL runs down the outside of your knee and the MCL attaches on the inner side of your knee. These ligaments help prevent too much side-to-side motion, think of them like a natural knee brace.

But these ligaments are strictly passive. Meaning, they aren't able to contract to provide more support if you place extra pressure through the knee during high-impact activities like, running or jumping. This can lead to the ligament rupturing and knee surgery depending on the severity of the injury.

Luckily for us, we have other supportive structures around our knees. The muscles running down our Femur and up our Tibia help pull and create a supportive structure that can withstand significant forces. This would include your Gastroc-Soleus (also called your calf muscle), Quadriceps, Popliteus, Hamstrings, and even the hip muscles. Unlike ligaments, these muscles can adjust to support to your activities.

Your calf muscles are much bigger than you think. They start at your heel and attach above your knee joint. Your Popliteus muscle runs underneath the calf in the back of the knee, helping to lock the knee in place and prevent excessive rotation. Your Hamstrings arrive from the opposite direction, traveling down your thigh and attaching across the knee. These three muscles provide reinforcement over the back of you knee joint.

Quadriceps are a massive muscle that attach to your pelvis and ends in your knee cap. The front and outside of the knee joint becomes reinforced by the Quadriceps, which expands to cover almost the entire outside of your thigh. Your IT band, which is a ligamentous structure running down the outside of your thigh, runs with the quadriceps to attach to the outside of your shin bone. This reinforces the LCL, but more importantly the IT band attaches to your hip muscles, allowing the hip to support the knee more directly.

Intra-articular Parts

The most infamous ligament inside your knee capsule is the Anterior Cruciate ligament or ACL. Your ACL runs in-between your Femur and Tibia, keeping the shin bone from sliding forward. Your Posterior Cruciate ligament, or PCL is another ligament that crosses the ACL to pull in the opposite direction. The PCL keeps the Tibia from sliding behind the knee.

Together, these passive ligaments create a stable base for your knee, limiting translation (or sheer) and rotation. Tearing of the ACL is most common of the two ligaments. This causes the Tibia to slide away from the Femur, making your knee unstable.

Tearing these ligaments at a young age usually involves surgery to reconstruct the ligament. But even with the reconstructed ligament, a torn ACL or PCL will place you at increased risk for developing arthritis within the knee joint.

Another important supportive structure for your knee is the meniscus. You have two menisci inside your knee joint:

- One lays on the inner or medial side.

- The other on the outside of the joint.

These structures are made of cartilage and act as cushions in the knee joint. They also attach to your ACL and PCL, reinforcing the knee in the front and back.

The meniscus can become damaged over time with wear and tear, or acutely, usually when the knee is rotating and in a bent position.

Some injuries can heal on their own but if the damage is too severe, it may require surgery. Usual surgical candidates involve more complex tears that "catch" in the knee joint. This leads to "locking" which is when the knee bends but cannot straighten because the meniscus tear is catching.

Another important part of your knee joint, which runs over the ends of the Femur and Tibia as they meet within the knee joint, is your Articular cartilage.

Articular cartilage creates a smooth surface on the end of the bone, protecting the bone and decreasing friction within the joint. Over time, depending on what the knee has been put through, this cartilage can wear out. This natural deterioration causes pain especially in the morning, pain with weight bearing, and constant stiffness. You also hear what is called Crepitus, or grinding, and popping of the knee joint as it bends and straightens.

This condition's technical term is Osteoarthritis, which most people just call "arthritis". Like we said earlier, knee arthritis involves three main areas of the knee, the Medial and Lateral (inner and outer) compartments of the knee, and the capsule of the Patellofemoral joint. Osteoarthritis tends to form initially on the inner compartment at the knee, but can quickly cause pain in all of the compartments.

This Articular cartilage is within the knee joint capsule itself. Surrounding the cartilage is the synovial fluid or the"oil" of the knee joint and around the inner joint is the lining the of the knee capsule.

Believe it or not, the Articular cartilage is not a huge pain producer. We know this because two knee surgeons were bold enough to open up their own knee joints while awake! They poked at all the different parts of the knee to see what hurt the most. What they found was the articular cartilage was not very painful. They theorized the knee pain from arthritis is actually from inflammation of the synovial fluid and of the knee capsule.

The reason this is so important is if someone says you have "bone-on-bone" in the knee, that does not necessarily mean you need a knee replacement. Don't get us wrong, some people really do need a knee replacement. But if you can put off a knee replacement for one to five years, it makes a huge difference. Why, you ask? Because knee replacements have a typical lifespan of 15 years. If you get a knee replacement in your 50s, you may need it donetwo more times

Each time a knee replacement wears out and needs to be redone, the revision takes up more and more bone. This leads to increased risk of failure of the replacement. If Physical Therapy can help you prevent a knee replacement, try it!

Patello-Femoral Joint

We know what your are thinking, the Patello-Femoral joint is a very fancy way of saying knee cap. But trust us, this joint deserves the fancy name, because it does a lot. Your Patella (or Patello-Femoral joint) sits over your Femur (The Femoral part of the Patello-Femoral joint) at the knee joint, protecting the Articular cartilage of the Femur. The inner surface of the Patella is lined with the same Articular cartilage, allowing the knee cap to glide across the knee.

The Patella sits inside a inner web of connective tissue called your Retinaculum, which attaches to many of the structures we discussed earlier. The main attachment to the Patella is your Quadriceps. The Quadriceps are actually made out four different muscles called:

- Vastus Lateralis,

- Vastus Medialis,

- Vastus Intermedius, and

- Rectus Femoris.

The heads of these four muscles blend into the quadriceps tendon, that attaches to your knee cap. The knee cap also attaches to the Tibia via the Patellar tendon.

The Quadriceps tendon and the Patellar tendon, are both used when the Quadriceps pull on the Patella. In high demand activities, the Quadriceps in turn put more stress on both tendons. If your body is not accustomed to this pull, these tendons can become irritated and painful. This is also called knee tendonitis, but may be called a more specific name depending on the tendon.

You may ask yourself why do your Quadriceps need a kneecap? Believe it or not, your Patella dramatically increases the force of your Quadriceps. It's a personal pulley system for your body and one of the larger force producers you have. This leads to the Patella dealing with a significant amount of force.

Some studies say it may handle up to five times your body weight.

Due to all of these different muscles, ligaments, and tendons connecting to the Patella, this joint can move in variety of directions. Your kneecap glides side to side, up and down, tilts and rotates in all directions. Sounds awesome right? We agree. But the Patella becomes an issue when it is pulled too much in one direction, by either a tight muscle, ruptured tendon or ligament, or even improper running technique. This can lead to excess stress in certain areas of the kneecap as well as pain.

Excess stress at the Patella, or constantly over utilizing the joint, may put you at risk for developing arthritis. This develops underneath the kneecap where the third compartment of the knee is located.

Proximal Tibial-Fibular Joint

Your fibula is a long bone on the outside of your shin that makes up part of your ankle. What most people don't know, is this bone runs all the way up your shin to make up part of the knee. The Proximal Tibial-Fibular joint, or TFJ, is a much more stable joint than the other knee joints. However, as the knee bends and straightens the Fibular head at the top of the Fibula glides forward and backwards.

In being such a stable joint, the Fibular head becomes a stable base for various ligaments and tendons to attach. This includes part of your Hamstrings, Popliteus, and Lateral Collateral ligament. In rare circumstances, this joint can become a source of pain or disfunction if the joint becomes unstable, or the head of the Fibula fractures. A trained Physical Therapist should be able to properly evaluate this joint and see if further assessment from an orthopedic doctor is necessary.

In Summary

As you can see, the knee joint is not simple as you may have thought. But even if you hate anatomy and physiology, having a basic knowledge on these structures can give you a leg up on your rehab goals. You can't fix a problem without knowing what the problem is.

Still don't get it? That's okay! What isn't okay is trying to push through knee pain for years and waiting until it is too late to get it fixed. We've seen plenty of patients that if they were seen earlier, may have avoided surgery.

If you do have a knee problem, our best advice would be to see a Physical Therapy right away. The best case scenario is we help you avoid surgery or more pain. Worst case scenario we get you a head start on your rehab for after your surgery. Either way it's a win.

If you have any further questions, reach us in the area below. We are happy to help you get back to your activities in any way we can.

Physical therapy for knee pain in Columbia and Baltimore, Maryland

If you have knee pain reach out to our office today!